The Kings of the Sealand sound like they come straight out of a fantasy novel but it’s the name given to a royal dynasty who ruled a swathe of Bronze Age Iraq for almost three centuries (ca. 1730-1460 BCE). Archaeologists know almost nothing about the Sealand Kings or their kingdom; all we have to go on are a tiny number of ancient texts, mostly written about them by other rulers. We know they controlled the swampy land around the head of the Persian Gulf, including several of the great ancient cities of southern Babylonia, and we know that they thoroughly annoyed the Kings of Babylon from whom they’d wrestled their kingdom.

In some ways, the Sealand kingdom is a distant ancestor to the many independently minded communities to have thrived in the Iraqi marshes which, like the English Fens, have always resisted external control and provided a refuge for rebels.

On the ground, Sealand period remains had never been firmly identified at any archaeological site, but new excavations by a British-Iraqi team have finally found a settlement of the elusive Sealand state. The Ur Region Archaeology Project, in partnership with the University of Manchester and Iraq’s State Board for Antiquities and Heritage, completed excavation at the site of Tell Khaiber this spring. The project was one of the very first international missions to return to southern Iraq in the post-Saddam era, helping to pave the way for other archaeology teams.

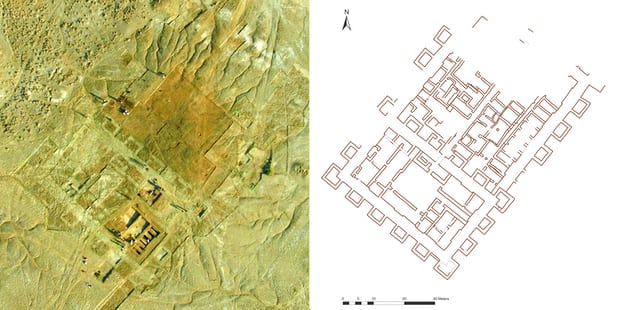

Tell Khaiber lies close to the modern city of Nasiriyah and the ancient city of Ur. There’s not much to see on the surface; just an almost imperceptible bulge in the flat, brown mud where centuries of settlement debris have left a lump. It took aerial images to truly reveal Tell Khaiber and the extraordinary building at its centre.

We only finished tracing the building’s plan in March 2017 but the unusual nature of the ground plan was obvious from the start. The building is huge, covering over 4400 m2, dominating the small settlement. It’s surrounded by a massive mudbrick wall around 3.5m thick, it has just one entrance and its exterior façade is ringed with close-set towers. The building is highly unusual for Bronze Age Mesopotamian architecture and the arrangement of perimeter towers has no known parallel in the region.

So what was this building for and why did it need to be so heavily fortified? We only have partial answers at this stage, but a lot of them come from an archive of inscribed clay tablets found scattered through the rooms of the building’s southern corner. It’s also these documents which place the building squarely in the Sealand kingdom; the few which are dated come from the reign of the eighth Sealand king, the excellently named Ayadaragalama (‘Skilful son of the stag’) who ruled the Sealand around 1500BCE.

Digging up clay tablets is not that fun. In this case they were made of unfired clay; dark brown and slightly soft, like a bar of chocolate. If you touch a tablet with a tool it leaves a mark to go with the hundreds of little surface marks which make up the ancient text. If you scrape a trowel across the surface of a tablet you’ll scrape off the text and the words someone wrote there three and a half thousand years ago are gone forever, and the conservator shakes her head sadly and the epigrapher stops talking to you. It didn’t help that the tablets were broken and mixed up with crushed mudbrick rubble which is remarkably similar in texture and colour, and that if you take too long getting them out of the ground they’ll be split apart by monstrous, fast-growing salt crystals.

Read More: Castle of the Sealand kings: Discovering ancient Iraq’s rebel rulers