With another version of The Mummy menacing cinemas, the “curse of the pharaohs” is back. Again. Hollywood’s determination to put marauding mummies in our sights suggests we still haven’t reached “peak curse”, almost a century after the sudden death of Lord Carnarvon made headlines.

So why was the idea of ill-fated Egyptology so alluring in the 1920s, when Carnarvon and Howard Carter found Tutankhamun’s tomb – and why does it keep returning to haunt us? One answer is that our obsessions are never really about the ancient past. They arise from the perspective people develop at a given moment, as they use the ancient past to express their own anxieties – and aspirations.

The 1920s offers a case in point, as I explore in my new book. At the same time the treasures of Tutankhamun and the curse of the pharaohs caught the imagination of mainstream culture, two modernist movements (Pharaonism in Egypt, the Harlem Renaissance in America) were interpreting ancient Egypt in a very different way. To them, ancient Egypt was an inspiration to take seriously, not turn into a fun, or a fright, show.

King Tut

In November 1922, backed by the Earl of Carnarvon, Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun in Luxor’s Valley of the Kings. To the British press, it was the first positive news from Egypt in years. (Egypt had been a difficult “veiled protectorate” since 1882, and earlier in 1922 Britain had decided to let Egypt elect its own government while keeping hold of foreign affairs and the Suez Canal.) And so the world went mad for “King Tut”, as he was quickly dubbed.

In England and America, popular songs, stage shows, and fashion design all celebrated Tutankhamun, as did advertising for everything from biscuits to cigarettes. There were Tut-themed balls in New York, student hi-jinks at Cambridge University, and a life-size recreation of the tomb’s antechamber built for the British Empire Exhibition in 1924 and seen by more than 27m people at Wembley Stadium, which was built for the purpose.

Call it Tut-mania, as many people do, but there was a certain method beneath the madness. The more King Tut could be treated as “one of us”, with “us” being white Euro-Americans, the more it seemed like he belonged to “us”, too, along with the rest of ancient Egypt. What better way to make a claim on culture than commodify it? Even news coverage and photographs of the tomb were for sale: Carnarvon gave The Times (of London) exclusive access to the find in return for a share of its profits. That riled other news outlets – including the thriving Egyptian press, suddenly banned from reporting a discovery in its own back yard.

Other Egypts

But neither Carnarvon nor Carter had thought about how much this rare find – the only royal burial discovered more or less intact – would mean to modern Egyptians. Poets and playwrights lauded the resurrection of Tutankhamun, comparing it to the rebirth of Egypt itself after centuries of slumber. The movement for an independent Egypt went hand-in-hand with an artistic and literary movement known as Pharaonism (Fir‘awniyya). No one could dispute the might of the Egyptian pharaohs. Rulers such as Ramses or Cleopatra, plus symbols such as sphinxes and pyramids, were harnessed to express the ambitions of the new state – and the antiquity of its roots.

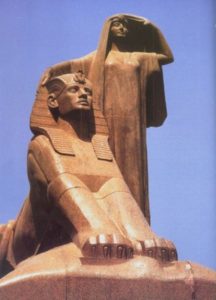

Nobel prize-winning novelist Naguib Mahfouz, who had witnessed street uprisings against Britain in his childhood (and visited the Cairo Museum), used ancient Egyptian themes in his first novels, while the Paris-trained sculptor Mahmoud Mukhtar raised public subscriptions for his colossal sculpture “Nahdet Misr”, “Egypt’s Renaissance”. Carved, like the lid of Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus, out of red granite from Aswan, the sculpture pairs a sphinx and an idealised image of Egyptian womanhood. It now stands outside Cairo University – an institution whose founding the British administration had opposed.

The antiquity and independence of ancient Egypt spoke to other 1920s cultural movements, too – including the group of African-American writers and artists known as the Harlem Renaissance. “Egypt” and “Ethiopia” were both synonymous with an Africa free of European control: Egypt because of its ancient history, and Ethiopia because it had fought off an Italian invasion in 1896.

“Ethiopia Awakening” was the title of an Egyptian-themed statue by Philadelphia-born Meta Warwick Fuller, who had studied with Rodin in Paris. It represents a woman with a beatific expression, black physiognomy, and a pharaonic head-scarf, unwinding herself from the constraints of mummy bandages. Cast in bronze, the statue featured in the “Colored Section” of the America’s Making Exposition in New York in 1921, organised to celebrate immigration. Although African-Americans had been forced migrants in slavery, organiser WEB DuBois saw a chance for the exposition to promote their contribution to the US. Meta Warwick Fuller turned a mummy into a force for good: there is no curse or vengeance in her Ethiopia sculpture, just freedom – or the longing for it.

Egyptomania

We admire the 1920s as the Jazz Age, an era when what we think of as modern Western mores sprang from the ruins of war. But what looks more sophisticated in retrospect: Britain’s imperial adoption of Egyptology and the Western commercial mania for mummies and King Tut, or the creative output ancient Egypt inspired in Egyptians and African-Americans, in the same decade?

“Ethiopia Awakening” looked to a future based on dignity and equality, as did “Nahdet Misr” – while the British Empire Exhibition, with its Tutankhamun replicas, looked to the rapidly setting sun of British imperialism. Perhaps any curse in Carnarvon’s untimely death wasn’t from what he and Carter discovered, but what they overlooked – that theirs was not the only “ancient Egypt” out there.

It’s a useful caution that we should look for the method that might lie behind any Egyptomania today, whether that entails movie franchises or museum displays. Turning sacred objects (which is what mummies were, to the people who made them) into light entertainment hardly flatters any of us. Nor does imagining the Middle East as an origin-place for horror and a threat to white masculinity, this time in the guise of Tom Cruise. If we are doomed to rehashing The Mummy, in other words, it’s a curse not of Egypt’s making – but ours.

More: The Mummy: what our obsession with ancient Egypt reveals