by

Our perceptions of the ancient world are shaped by the way surviving relics appear in the present day. The cool white marble beauty we attribute to Classical Greek and Roman statues arises from the long faded lifelike paint these statues once bore. The bright limestone of Maya pyramids today shines against the surrounding background of deep jungle green, yet these buildings were once painted from top to bottom in deep reds, blues and greens. As for the imposing and regal black cat of ancient Egypt, those cats didn’t look the way you think either.

The objects of the ancient world that happen to survive to the present are inevitably the most durable objects. Durability, however, is no guarantee that these objects are good representations of our ancestors’ past behaviors or interests. Circumstantial evidences suggests, for example, that the rulers of the ancient Maya cities kept numerous bark paper books. The humid jungle environs of these cities, however, ensured that those books could not survive in a readable form. Similarly, the durable stone and metal sculptures of ancient Egyptian cats has shaped our assumptions of what those cats looked like.

The iconic image of an Egyptian cat arises from objects such as the leaded bronze statuette from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, pictured below. Numerous statuettes such as this were made during Ancient Egypt’s Ptolemaic and Late periods as vessels to hold the mummified remains of domesticated cats. The commonality of this form, and the dark coloration of the metal, lends to the popular impression of ancient Egyptian cats as black furred.

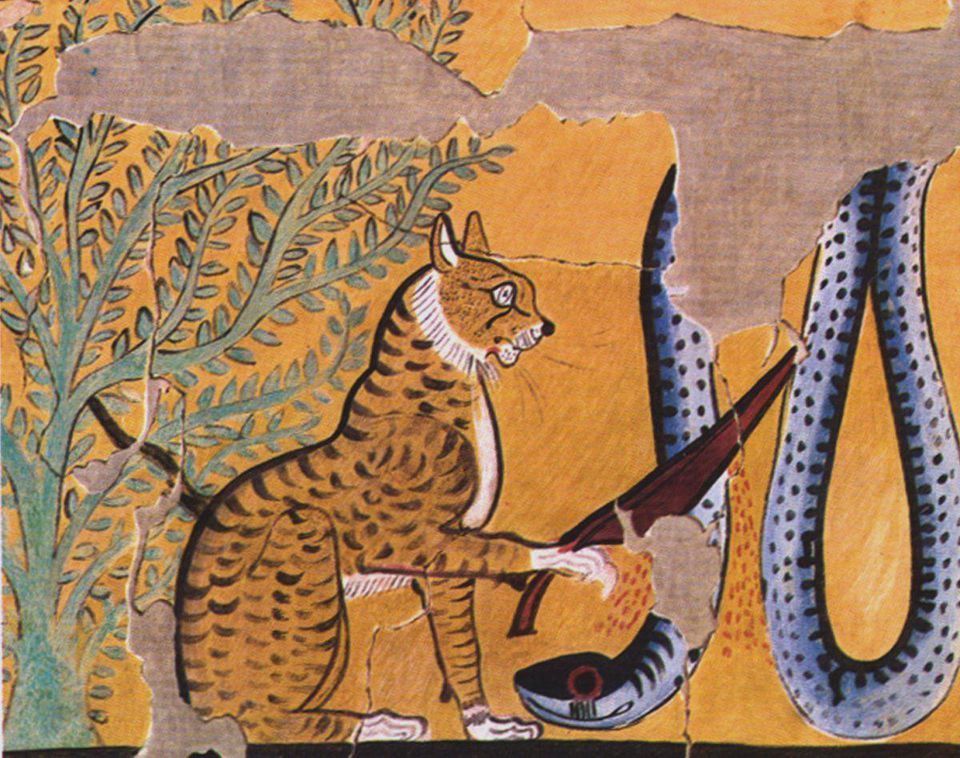

If we turn to the less well-known record of Egyptian tomb paintings, however, we find cats of a distinctly different appearance. The facsimile image below presents a cat with a distinctively tabby coat from the walls of the Tomb of Sennedjem at the site of Deir el-Medina in Upper Egypt. The fantastical nature of the image with the cat decapitating a serpent using a blade is an often-repeated visual reference to The Egyptian Book of the Dead; wherein a cat is depicted defeating the divine enemy of the sun god.

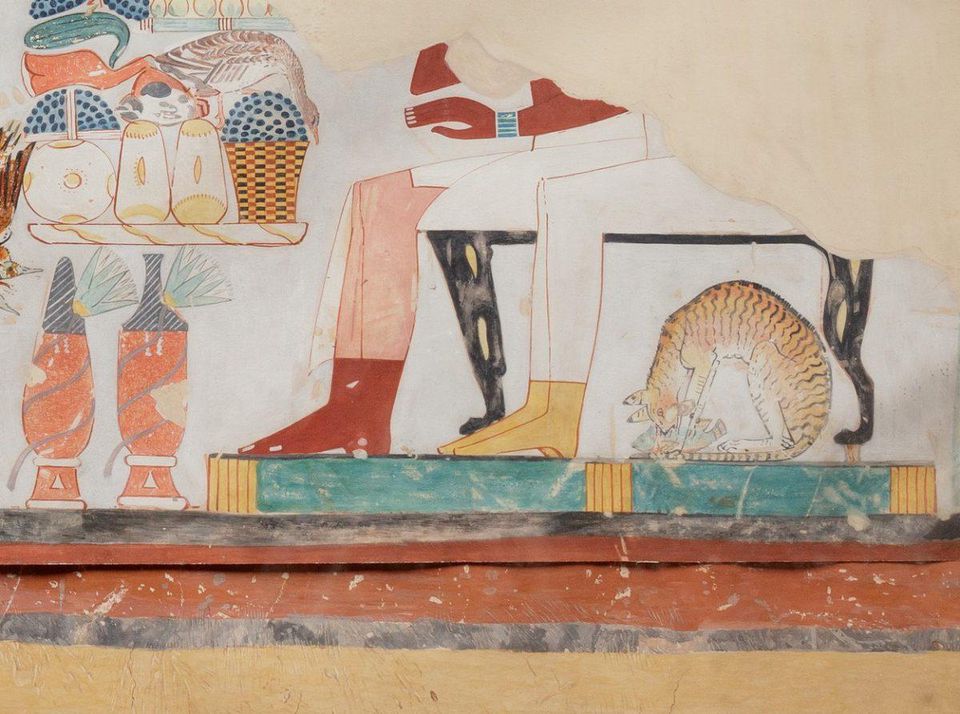

An image from the Tomb of Nakht, Thebes, Upper Egypt, presents us with a decidedly more domestic scene of another tabby cat. This cat feasts upon a fish as it sits underneath the chairs of its human companions. This pattern of cats with tabby coats continues throughout Egyptian mural art, thereby presenting a very different image from the austere black cat suggested by statuary.

The presence of tabby cats in ancient Egypt is further supported by a recent genetic study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution. In this study the authors confirmed that genetic evidence suggests the blotchy coat patterns common to many domesticated cats today did not emerge until the 18th century. The scientific findings were bolstered by a study of not only Egyptian paintings, but depictions of cats from many different cultures. This work found that throughout the ancient world “cats’ coats were mainly depicted as striped, corresponding to the mackerel-tabby pattern of the wild Felis silvestris lybica.”

Images have a powerful ability to shape the way we think, thus it behooves us to consider where those images come from. This is doubly important when dealing with the scant few images that survive from the ancient world. After all, our feline masters are unlikely to be pleased by servants who cannot properly depict their gods!

More: Cats In Ancient Egypt Didn’t Look The Way You Think