In newly published research, the two-person research team has found more than a dozen instances of hieroglyphic records from the Mayan Classic Period (250–909 CE) indicating that important events occurred within just a few days of an outburst of Eta Aquariid meteor showers, one of the celestial displays tied to the comet.

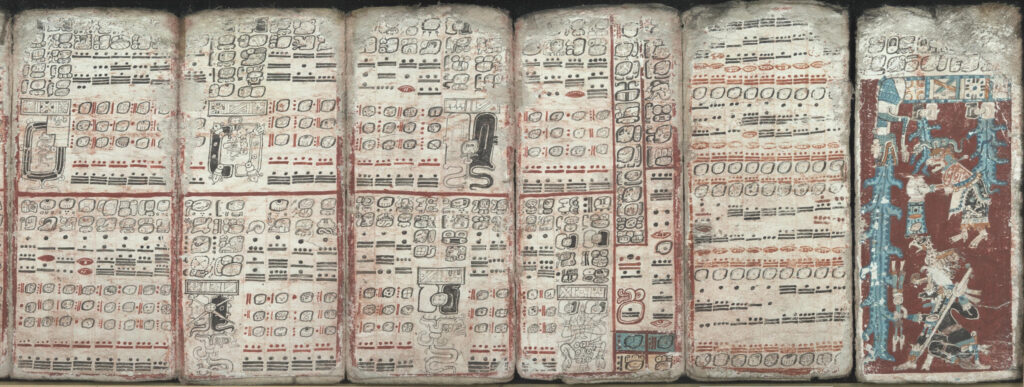

No Mayan astronomical records from that period survived the Spanish invasion, and the four surviving Mayan codices from later eras do not mention meteor showers. However, the researchers suspect that many significant historical events that coincided with meteor showers, like a ruler’s assumption of power or a declaration of war recorded in the codices and carved in stone monuments, are not chance overlaps.

If this new research is validated by further computational tests, it would help address a longstanding puzzle, said David Asher, an astronomy research fellow at Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland: How did the ancient Maya, a civilization that meticulously recorded astronomical information about Venus, eclipses, and seasonal patterns, fail to note meteor showers in their astronomical studies? They likely did record meteor showers, assert Asher and his colleague Hutch Kinsman, who has been an independent scholar of Mayan history and hieroglyphics for nearly 25 years, but the records were lost to us.

Modern Science Answers Puzzles from Ancient Times

Experts in Mayan hieroglyphic astronomy widely acknowledge that the Maya observed and recorded three types of common astronomical events during the Classic Period: phases of the Moon, solar and lunar eclipses, and the movement of Venus. Kinsman and other historians have wondered whether the Maya overlooked meteor showers or if they noted them.

Although mentions of the meteor showers themselves are missing from Mayan codices, Kinsman and Asher used computer models that track the motions and interactions of orbiting objects to calculate dates when the Eta Aquariid meteor shower, born from remnants of Halley’s Comet, would have been visible to the Maya during the Classic Period. They checked their calculated meteor shower dates against Chinese astronomical records from the same time period.

Halley’s Comet leaves behind a trail of would-be meteors when it passes by Earth about every 75 years. The comet debris can remain in orbit for hundreds or thousands of years before entering Earth’s atmosphere or may never intercept Earth at all. Asher, an expert in solar system dynamics, explained that when modern astronomers try to predict the positions of small chunks of rock and ice hundreds of years after they broke off from a parent comet, they “need a comet whose orbit was well known before the time when you hypothesize that the Maya might have observed the meteor outburst. Halley’s Comet fits the bill quite nicely,” he added.

The comet’s remnants produce a few very predictable and large meteor showers, including the Eta Aquariid shower, which is typically observable from April to May across northern to southern midlatitudes. “The Eta Aquariids were the natural choice for research,” Kinsman said.

Meteor Outbursts Coincide with Ascents to Power

After the researchers predicted dates during the Classic Period when Eta Aquariid outbursts likely occurred, they then searched for significant events recorded in Mayan hieroglyphics that took place on or near those dates, attempting to see if the Maya, like other ancient civilizations, used meteor showers as portents of greatness.

“The approach we’ve taken is to look for coinciding dates,” Asher explained. “There are dates on the Maya[n] inscriptions, and Mayanist experts can tell us what they are.…Orbital computations give dates when meteor outbursts occur[ed].”

The researchers’ models suggested 18 different Eta Aquariid meteor outbursts that were likely visible to the ancient Maya during the Classic Period. A third of those meteor showers occurred within 4 days of a ruler ascending the throne, and other showers correlated with declarations of war, important people traveling between cities, or agricultural or industrial activities. “With coinciding dates, we start to have evidence rather than (interesting) speculation,” Asher said.

The strongest meteor outburst that Kinsman and Asher pinned down to a particular date occurred on 10 April 531 CE, when three different comet trails intercepted Earth at the same time. They indicate in their paper that this extreme outburst was “likely the most intense that the Maya would have seen during the Classic Period.” Four days after the 531 CE Eta Aquariid outburst, the ruler K’an I ascended to power in Caracol (in modern Belize).