Signs of a culture that disappeared without a trace seven centuries ago have now been found in a rather unusual place – in the genetic material of domesticated birds.

Mitochondrial DNA taken from the remains of ancient turkey bones seem to suggest the population simply packed up and moved, confirming accounts of their descendants living on in the US Southwest.

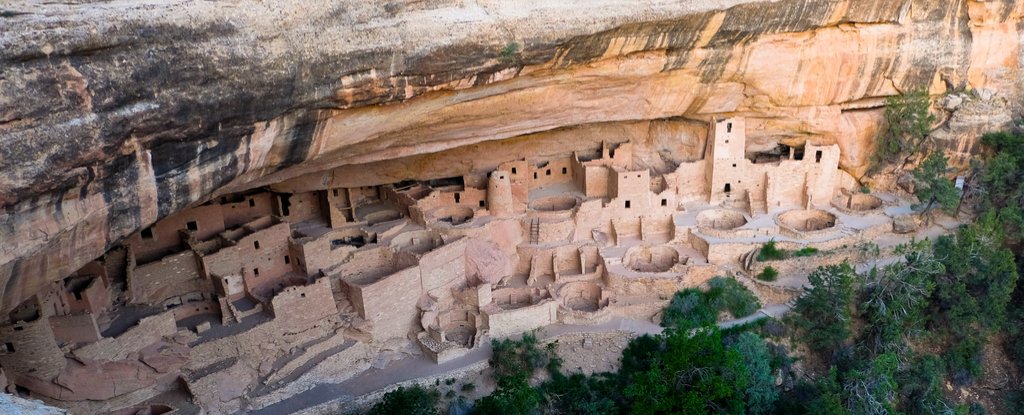

The Ancestral Puebloans were members of the Pueblo people who once occupied the Four Corners region of the Southwestern United States.

Around the thirteenth century, members of this culture built a settlement of magnificent structures made of sandstone blocks and timber into the sides of a cliff in what is now Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park.

Then, a century later, they abandoned it. Tens of thousands gone in just a few decades.

The exodus has left archaeologists with something of a mystery to solve, one made more difficult by the complex cultural values surrounding the digging up of human remains regarded by today’s cultures as sacred.

For modern Tewa Puebloan people living in the northern Rio Grande region of northwestern Mexico, the answer is simple; the Ancestral Puebloans – also called the Anasazi – simply packed up and moved.

It’s entirely possible that political upheaval and cultural conflicts forced the Ancestral Puebloans to abandon their city and resettle several hundred kilometres east, but conflicting material evidence still leaves room for questions.

Without access to human bones to study, a team of American researchers has now studied the next best thing – the bones of their animals.

The researchers speculated that comparisons between populations of animals such as dogs and turkeys could reveal signs of an ancient migration, one that could provide circumstantial evidence of the Ancestral Puebloans’ movements.

To test their hypothesis, they extracted the mitochondrial DNA from hundreds of turkey bones gathered from Mesa Verde, as well as a few dozen dog bones, and tested what are called haplogroups.

Haplogroups are clusters of genes from a single parent that tend to cling together as they’re inherited, making them useful codes for comparing ancestry.

Unfortunately the dog remains were a bust. No bones could be identified from post-migration sites in the northern Rio Grande, and DNA sequenced from pre-migration remains didn’t show much of a difference.

The turkeys, however, indicated an influx of fowl took place over seven centuries ago.

Prior to 1280 CE, the turkeys from the Mesa Verde area and northern Rio Grande had completely different matriarchal lineages.

After, the Rio Grande turkeys started to carry Mesa Verde haplotypes; strong evidence of a mixing of stock.

Not all of the turkey DNA was in great shape, and some odd contrasts between the haplogroups mean the evidence is less ‘smoking gun’ and more ‘luke-warm barrel’.

Still, the results don’t rule out what many modern Pueblo people believe, adding a degree of confidence to the migration hypothesis.

“People don’t need their own history to be verified by archaeology, but they are interested in having science work alongside them, not in spite of them,” tribal historic preservation officer Bruce Bernstein told Michael Price at Science.

“This is a good example of work that fills in some gaps in what Tewa people have talked about.”

The bones support the view that around 1270 CE, Ancestral Puebloans experienced hardship, whether in the form of a changing climate, political upheaval, drought, overpopulation, or a mix of factors.

They gathered their turkeys (and no doubt a few other things) and journeyed east into the lands that would one day become northern New Mexico, where they and their birds mixed with smaller numbers of other distantly related populations to become today’s Tewa people.

It’s far from case closed on this fascinating piece of America’s past, with the history of the Ancestral Puebloans continuing to inspire debate for a long time to come.

This research was published in PLOS One.

More: Evidence of a ‘Vanished’ Civilisation May Have Been Rediscovered in The US